How Spain manages 100% primary care access

How is it that 100% of people in Spain have access to primary care?

I’ve been in Barcelona for a week to better understand their system—part of a longer journey I’ve been on studying health systems with strong primary care.

Spain is one of WHO Europe’s primary healthcare demonstration sites because of their established team-based model. Their model of care originates from the Spanish Primary Health Care Reform Act, passed in 1985, which was inspired by the principles of the WHO Declaration of Alma-Ata. It took 20 years to implement.

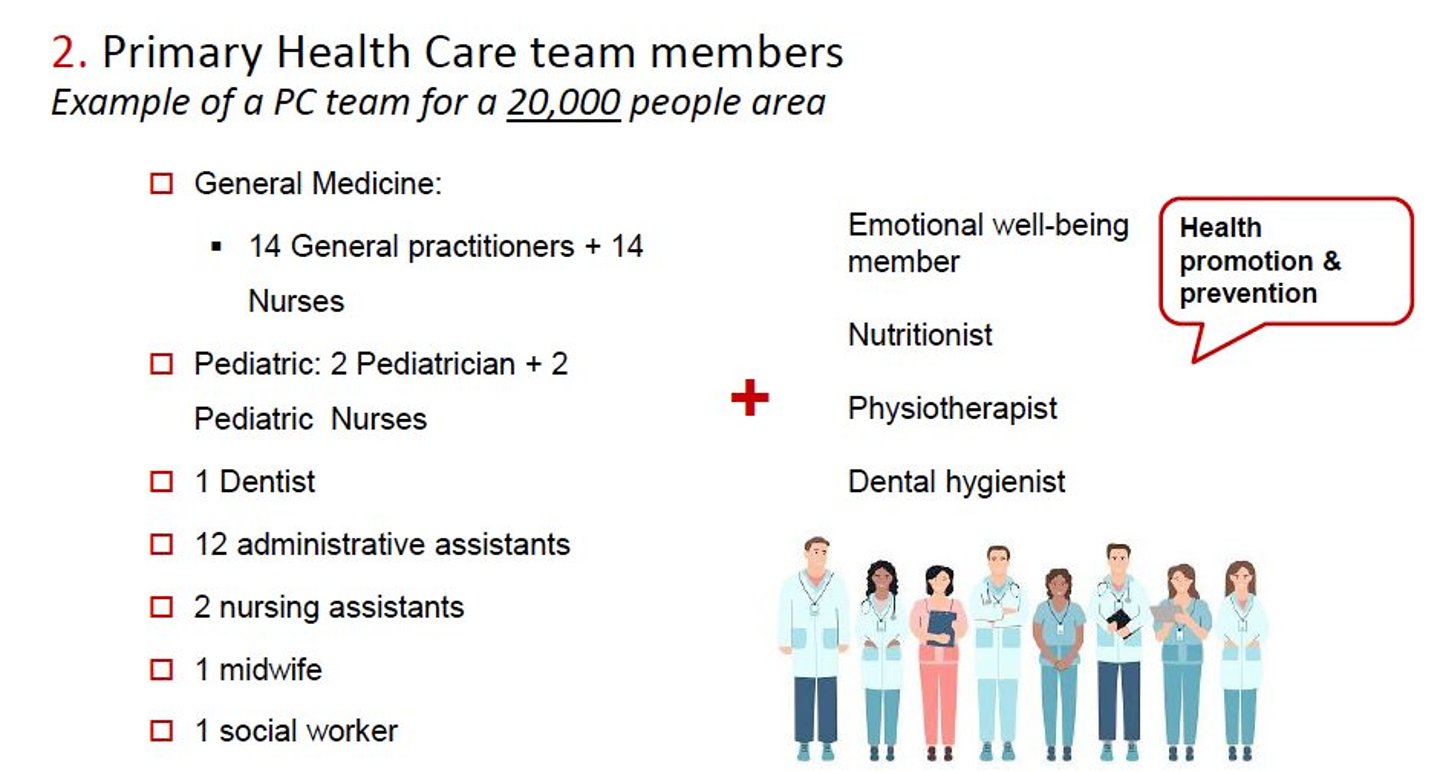

Today there are multidisciplinary teams across the country based in primary healthcare centres that serve people living in the surrounding geography.

Health delivery is decentralized in Spain. Standards and laws are set at the national level and each of the 17 autonomous regions are responsible for implementation and care delivery, not unlike our model of decentralization in Canada.

Across Spain, each primary care centre has a catchment area and people in that area know they can attend the local centre. People can choose a different centre if they prefer but it seems that is not usual. Centres are open 8 a.m. to 8 p.m. No resident is turned away.

Centres never say they are full. If they are short doctors or other staff, it means existing staff have a higher caseload. It’s worth mentioning that Spain has about 1.8 times the number of doctors per capita compared to Canada!

Read: Dr. Tara Kiran: How the Dutch ensure 95% of citizens have a family doctor

Funding for each health centre is updated regularly by the region based on population demographics including age and socioeconomic status.

In Catalonia, where I visited, each patient who registers at the centre is assigned a doctor and a nurse who follows them. Doctors and nurses commonly work in pairs, serving the same roster of patients. Patients can choose their doctor or nurse and switch about once per year. Managers try and even out the case load between the different doctors so if one has a higher roster, a patient likely cannot choose them.

POSTS FROM SPAIN

Read all of Dr. Tara Kiran’s three-part series:

Doctors (and other staff) are on salary and paid to work 37 hours a week. Shifts are typically 8 a.m. to 3 p.m. or 2 p.m. to 8 p.m., Monday to Friday. After hours or weekend work is extra pay. And yes, doctors, like all staff, have vacation, sick leave, and a pension. A portion of doctor and nurse pay relates to attainment of quality measures (more on that later).

The centre doesn’t just serve those who walk in to register, but also those who are home bound or receiving long term care in the catchment area. Doctors and nurses do home visits to serve them. To me, this is a key point. The most vulnerable and high-risk patients are getting good primary care alongside the rest of the population. And the primary care team is grounded in the community it serves.

The core dyad in the primary care team is the doctor and nurse. In Catalonia, family doctors typically roster 1,400 citizens and nurses would have similar size panels.

I should mention that health centres have both family doctors and pediatricians. Family doctors care for patients 15 years old and up and pediatricians for those under 15. The focus of my visit was on family doctors but the context of the broader centre applies to both.

On a day-to-day basis, doctors and nurses each work quite autonomously. Nurses are responsible for stable chronic condition care. They counsel, monitor and assess patients to prevent complications from their chronic condition. They use checklists embedded in the EMR that largely follow Catalonian clinical guidelines. They can order needed lab tests and can suggest medications for the doctor to prescribe.

In addition, nurses also support acute care, home care and long-term care. In one of the centres I visited, they have worked on a triage manual to help receptionists know whether an acute issue should be booked with a doctor or nurse. Knowing where to book a patient with a chronic issue seems standard in all teams.

Most visits seen by a nurse are resolved by a nurse. If a nurse has a question for the doctor, they can of course consult them in the moment or at a later time. But unlike in Canada, there are few double visits (where a patient sees both the doctor and a nurse).

In Spain, nurses do a four-year university degree. After that, they have the option to take a state exam to access an additional two years of training in primary care. About 10% of primary care nurses have this extra training.

Teams also have social workers who largely deal with social issues, not mental health counselling. Dentists are publicly covered and also integrated into the primary care team.

In the last few years, teams have expanded to include a psychologist, a physiotherapist, a dietitian and dental hygienist. These relatively new positions are community oriented, supporting self-management and health promotion for people with milder illness. They run group programs for community members like workshops on low back pain, shoulder pain, anxiety, insomnia and cardiac health.

I should also mention what is not done in primary care. Breast and colorectal cancer screening are done by public health. Community pharmacists support distribution of colorectal cancer screening kits. Pap tests are done by the women’s health team and use of HPV self-sampling is common. Patients with serious mental illness are followed at mental health centres that have psychiatrists and mental health counsellors.

Dr. Tara Kiran is a Toronto family doctor at St. Michael’s Hospital and the University of Toronto and leads OurCare—the largest pan-Canadian initiative to engage the public about the future of primary care in Canada.