How the Dutch ensure 95% of citizens have a family doctor

In the Netherlands, more than 95% of people have a family doctor. That’s why I was there on an eight-day tour last month—to understand how their system works and bring back lessons that can help us improve primary care in Canada.

I was there with Rosemary Hannam from University of Toronto - Rotman School of Management. We arrived in Amsterdam in the morning and took the afternoon train to Tilburg where we met with Joël Gijzen and Nathalie Schoonhoven, two executives from CZ, one of the Netherlands largest insurance companies.

The Dutch have a unique model of ensuring health coverage for their population. All residents are required to purchase health insurance from private insurers—if they don’t comply there are fines. If they can’t afford the modest premiums, the government provides the funds. Most of the overall financing is public (e.g. from taxation) and not from the modest premiums.

Posts from Netherlands

The private insurers are nothing like private insurers in the U.S. Nine of the 10 insurers are non-profit co-operatives (including all four major ones). They are obligated to accept all applicants, provide everyone with the standard insurance package (set by government) and charge all policyholders the same fees. Access to a GP is part of the standard package.

This social health insurance system is founded on principles of social solidarity, just like medicare in Canada. But in the Dutch model, there is managed market competition between insurance companies (and between the providers they contract).

Insurance companies are obligated to find their customers general practitioners. They contract with GP-owners of practices to provide care for their customers. The contract specifies the payment and obligations. Insurers carefully monitor their list of customers to ensure everyone who wants a GP, has one.

Read: Read the full four-part series: What a difference Denmark makes

Generally, 70% to 75% of GP payment is via capitation (based on patient age and neighbourhood deprivation ) with the remaining largely fee-for-service.

The “model” panel size for a GP practice (i.e. one full-time GP) is about 2,300. The standard pay is supposed to be adequate to cover average practice costs including rent, IT and office staff. GPs can ask for additional resources for managing chronic conditions and specific unmet needs in their community.

Interestingly, the GP fee rates are set nationally based on independent assessment of GP practice costs done by the National Health Care Institute. There is no negotiation between government and the medical association!

The contracts specify care must be to standards developed by the Dutch college of GPs. There are also national standards on acceptable wait times for non-urgent care (“treeknorm“) which the insurance companies monitor. If customers complain that they can’t get timely care, the insurer investigates, provides warnings and eventually can end the GP contract.

It’s clear that the system is customer-oriented—a key ingredient shared with many high-performing system like the system in Denmark and the NUKA model in Alaska. It’s something we need more of in Canada.

Structural reasons

Of course, there are structural reasons why the Dutch system is much better than the Canadian system at ensuring everyone has access to primary care

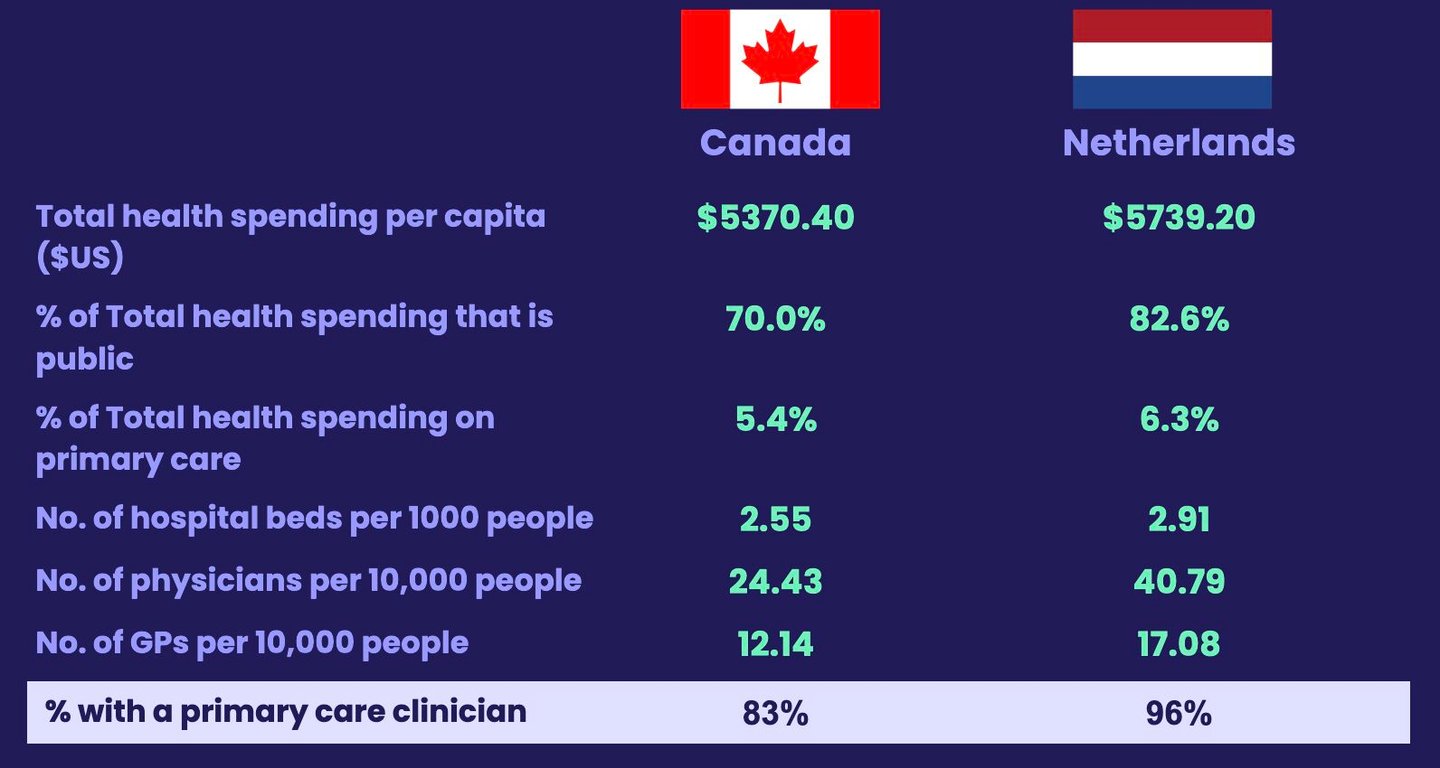

This slide beside here provides some key insights:

- They spend more on healthcare per capita

- More of their spending is in the public system

- They spend more of their total health budget on primary care

- They have 1.6 times the number of doctors per capita

In a paper last year by myself Heba Shahaed, Dr. Richard Glaziern and others, published in the Canadian Medical Association Journal, we compared Canada to nine high-income countries where more than 95% of the population has access to primary care. We found that Canada was at the bottom when it came to the per cent of spending that was public. Canada was also at the bottom when it came to the total number of doctors per capita.

Family doctors are generalists, and when there are fewer doctors per capita, there is a lot more demand for them to work in other areas of the system besides primary care--including caring for people in hospital. So even though the number of family docs we have may not look too different from our peer countries, it’s deceiving because many of our family doctors work in other parts of the system.

I have learned though that even here in the Netherlands they are worried about trends in the supply of GPs doing primary care.

The Netherlands has historically trained more than enough GPs to meet their population demand. But recent trends have them worried that they also may not have enough supply moving forward.

The executives we spoke to at CZ, said that fewer GPs in the Netherlands want to work as practice owners. Most prefer to be self-employed and take shifts in a practice during the day or take a shift in an out-of-hours centre.

Being a practice owner means you are responsible for running the business and being accountable to the insurer for accessibility and quality of care. It also means you are committed to staying in the same location for some time. On the other hand, being self-employed means you can work when you want to, have much less accountability and have no long-term commitment.

And about 60% of GPs work part-time so they estimate needing to train about two GPs to fill one full-time role.

These changes in how GPs want to work seems similar to what we’ve heard anecdotally in Canada.

Dr. Tara Kiran is a Toronto family doctor at St. Michael’s Hospital and the University of Toronto and leads OurCare—the largest pan-Canadian initiative to engage the public about the future of primary care in Canada.