In medicine, gender still matters, survey finds

The Medical Post Gender Equity in Medicine Survey, conducted online in June 2017, had 431 respondents. Survey respondents were recruited via the Medical Post’s daily newsletter, social media and direct emails to Canadian doctors in the Medical Post’s database. Who took the survey: 77% were Canadian physicians, 14% Canadian residents, 6% Canadian medical students and 3% other. Most of the respondents were female (74%) and 26% were male. As for where they worked, community (58%) was the most common while 37% worked in an academic centre. As well, 80% worked in an urban environment and 75% said they were a parent. Presented results may not equal 100% due to rounding or because “not applicable” responses were not included. The percentages of respondents who agree or disagree with a statement are the sums of the responses for “strongly” and “somewhat” agree or disagree.

The Medical Post Gender Equity in Medicine Survey, conducted online in June 2017, had 431 respondents. Survey respondents were recruited via the Medical Post’s daily newsletter, social media and direct emails to Canadian doctors in the Medical Post’s database. Who took the survey: 77% were Canadian physicians, 14% Canadian residents, 6% Canadian medical students and 3% other. Most of the respondents were female (74%) and 26% were male. As for where they worked, community (58%) was the most common while 37% worked in an academic centre. As well, 80% worked in an urban environment and 75% said they were a parent. Presented results may not equal 100% due to rounding or because “not applicable” responses were not included. The percentages of respondents who agree or disagree with a statement are the sums of the responses for “strongly” and “somewhat” agree or disagree.

It’s hard to believe in equal career opportunity as a female in medicine when you are consistently reminded of your gender. At least that’s Sally Kang’s impression. When the medical student at the University of Toronto (starting third year in August) applied for a summer surgery scholarship several months ago, the male interviewer asked, “Have you thought about family medicine?” She reminded the interviewer she was there for a surgery scholarship but the interviewer pushed further: “Are you sure you don’t want to do family? It’s definitely much more friendly—lifestyle-wise—for you.”

Kang said she was taken aback. “It just felt really uncomfortable to me.” She ended up not pursuing the scholarship. Kang said she feels like now that she’s in medicine, “I’m more reminded that I’m a female. Since I’ve started medical school and as I delve into different specialties, surprisingly, the more pushback I am getting (because of my gender).”

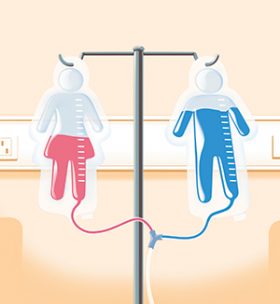

The interviewer may have thought his comments were in Kang’s best interests, but would he have asked a male medical student the same questions? Gender bias in medicine can be a subtle thing, but as we found when we asked hundreds of physicians and trainees in our Gender Equity in Medicine Survey, when it comes to career opportunity and advancement in medicine, gender still matters. Indeed, in response to the statement, “As my career progresses, I feel as though my gender plays an increasingly important role in determining my career opportunities,” 69% of female respondents agreed while 33% of male respondents agreed.

Medical schools in Canada are fairly evenly divided on gender (just slightly more women than men). Then something happens: as physicians are trained and begin working it appears as if something prevents as many females as males from advancing in their careers. Indeed, the gender gap in academic medicine was quantified at the research institute attached to St. Michael’s Hospital in Toronto in an article published in CMAJ Open in February 2017. The research team found that the institute included 30.1% women and 69.9% men—a 39.8% gender gap. Meanwhile, data from the Association of Medical Faculties of Canada show women do not fill half of the leadership in academic medicine. There are two female deans at the 17 medical schools in Canada and 22% of the full professors are women at the nation’s medical schools.

As well, there are multisite data from the Association of American Medical Colleges showing that women make up only 21% of full professors in the United States.

“Where are the women at the full professor level? In leadership roles at department levels? Chairs? Chiefs?” asked Dr. Reena Pattani, a general internist at St. Michael’s Hospital in Toronto. “Women make up about 25% or less of full professors, which you can’t account for purely on the basis of parental leaves or time delays—women have been comprising half of the medical student body since the (1990s).”

Mentor shortage

According to Dr. Pattani, the cause of the gap is multifactorial. It may be that a lot of key networking happens informally—at bars after work, sporting events—rather than through formal structures. If women can’t access these informal networks, they may not be considered for career advancement or opportunities when they are available.

Mentorship may also be a factor. When there are few women in the upper echelons, in terms of sponsorship, these women are already maximizing their resources to support junior women. There just may not be enough senior female sponsors for the number of junior women looking for one. Same-gender mentors can be important role models—it’s difficult to imagine being in a specialty, or occupying a leadership position, when you don’t see people like you occupying those positions.

The common advice to medical students about specialty choice includes: find something you like, something you are good at and something where you find people like you. To Kang, the second-year medical student interested in surgery, this advice falls flat. “When they say that, a part of me feels a bit hesitant,” she said. “Find my people. But what if ‘my people’—a woman, a minority—doesn’t exist?”

The issue of female role modelling in medicine was highlighted in an article in JAMA Internal Medicine in May 2017 that focused on the representation of women among academic Grand Rounds speakers. The paper found that women were much less likely to present at Grand Rounds than men, even after adjusting for their representation within different areas of medicine. Discussing the results, the researchers wrote: “Speaker selections convey messages of ‘this is what a leader looks like,’ and women’s visibility in prestigious academic venues may subconsciously affect women’s desires to pursue academic medicine. The lower a field’s female visibility, the more likely women are to consider male stereotypes necessary for success.”

Indeed, Mei Wen—currently about to enter third year of medical school at the University of Toronto—said she’s seen that firsthand. When she was in first year she attended a mandatory session on leadership as part of the CanMEDS framework. “By the end of the (three-hour) presentation I was shocked to realize that there was not a single video or photo of a female leader that was mentioned. I mean seriously? It’s 2015,” she wrote in a blog post. After the session, Wen brought her concerns to the lecturer, who was receptive to her feedback. But what does the omission of female leaders in a core leadership session say about a subconscious bias of “this is what a leader in medicine looks like”?

Perhaps male respondents, when applying for jobs within medicine, are less likely to be made aware of their gender, and thus less likely to see it as affecting their career opportunity? “The only occurrence I have had in my training or career where my gender put me at a disadvantage was as a male medical student being told I could not assist with a delivery during my obs rotation due to a request by a patient,” recalled Dr. Michel Chiasson, a family physician in Cheticamp, N.S.

Implicit bias

Dr. Arielle Berger, a geriatrician with the University Health Network in Toronto, said she believes implicit bias is the biggest barrier to equity and diversity in medicine—and to leadership in general. “We all walk through life with innate ideas of what makes a ‘good doctor’ or a ‘good leader.’ I think we tend to gravitate to people who are similar to ourselves, to our backgrounds, and that perpetuates future leaders being similar to past leaders. I don’t think anybody sits down and says to themselves, ‘I’m going to promote this man because I like men more than women,’ but I do think that there are subconscious beliefs at play when men are offered leadership roles more often than women.”

Gendered language and behaviours may also subtly shape a work environment to be less friendly to female professional advancement. Many physicians and trainees interviewed for this article stated that patients often refer to male medical students as “doctor,” yet females with the same level of training are more likely to be referred to as “nurses.” If the language that is used within a clinical workplace perpetuates a culture in which male physicians and trainees are assumed to be of higher rank, this likely affects a female physician’s real and perceived career opportunity in comparison to her male colleagues.

Dr. Kimberley Meathrel, a plastic surgeon in Kingston, Ont. said: “I have many patients who call me by my first name despite the fact that I never ever introduce myself by my first name and always introduce myself as ‘Dr.’ To assume it is OK to call me by my first name is a subtle undermining of my knowledge and skill by removing the title of my academic achievements—and this happens to my female colleagues all the time. It happens at conferences too—male panel members or speakers will be introduced as ‘Dr.’ and females by their first name. It’s daily, it’s ongoing, and these microaggressions add up to a hostile work environment and I suspect contribute to the burnout rates of female docs. It’s a never-ending struggle.”

Gendered expectations of work and lifestyle may be so ingrained that they affect the training process itself. Beyond being questioned about why they may want to pursue a certain training opportunity, female trainees sometimes feel they receive less rigorous training than male colleagues. According to emergency physician Dr. Melissa Yuan-Innes of Cornwall, Ont., “It can be subtle. For example, a urology resident noticed that a consultant would ask her about her husband or her weekend, but when her male compatriot came on, he’d quiz him mercilessly. The consultant was trying to be nice to her, but she knew she wasn’t learning as effectively.”

About the author: Emily Hughes is entering her third year of medical school at the University of Toronto. To complement her career as a physician, she is an aspiring journalist and has a background in campus radio hosting and production. Her motivation to work on this project came out of her surprise at the findings of a 2016 JAMA Internal Medicine paper, “Sex Differences in Physician Salary in U.S. Public Medical Schools,” which found that after multivariable adjustment, male physicians were compensated an average of $19,878 more annually than female physicians.